You can’t deny it: Canadian author Margaret Atwood is the queen of dystopian fiction. In The Heart Goes Last, she takes us to Positron/Consilience, a prison/city where you’re given a home and a good life, provided you never want to leave. Set against a post-financial-apocalypse backdrop, Atwood’s novel examines the question of consent with its broadest possible lens.

After the economy tanked, the U.S. turned into something that feels not unlike the Dust Bowl: an empty wasteland full of desperate people struggling to keep living day-to-day. I can’t recall a single tree in Atwood’s novel, although Consilience does have hedges for its residents to trim. Even so, everything feels dry and drained of life.

In this dismal world, Charmaine and Stan live in their car, which Stan hardly ever leaves, because someone — anyone — might steal it. She works days as a waitress. When they hear about the Positron/Consilience project — which promises furnished homes, good food, and clean living — it sounds too good to be true.

And, of course, it is. There’s plenty to suggest that the prison/city is not what it seems. You know that something dark and ominous swims beneath the bright plastic of its pseudo-1950s exterior. Speeches from the project head are obvious propaganda, complete with a 1984 kind of flair. Charmaine and Stan aren’t oblivious to these facts, but Positron/Consilience remains the best home they’ve had in recent memory. And so, they stay.

While The Heart Goes Last has plenty of content to open up conversations about what constitutes consent — from rape by deception and coercion to intentional manipulation of the brain’s sexual centers — Charmaine and Stan’s living situation begs the most interesting questions by far.

In We, Robots, Curtis White takes to task those who present adaptation to a changing world as a “choice.” Only people of privilege have the choice to pick up stakes and move; for the rest of us, it’s a necessity. He quotes Friedrich Nietzsche to drive home the point: “freedom of will is the invention of the ruling classes.”

This is the kind of choice Charmaine and Stan have. Join Positron/Consilience, or die. Stay in Positron/Consilience, or die. Leave Positron/Consilience, or die. In the end, it’s up to you to decide whether the couple has really had any choice at all.

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Read all my reviews and follow me on Goodreads!

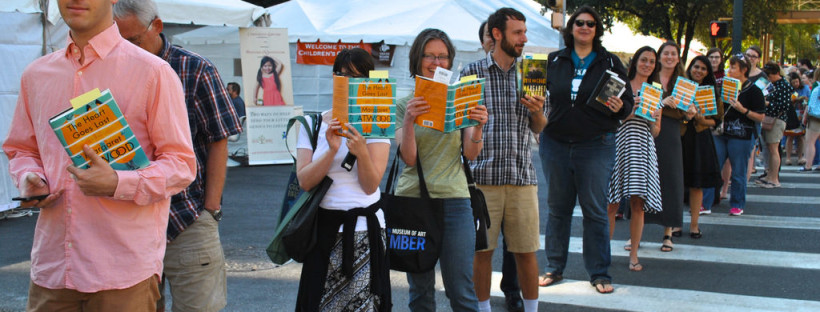

Image: Barbara Brannon/flickr